It's been 521 years since the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus "sailed the ocean blue/in fourteen hundred and ninety-two." Since then, there have been thousands of parades, speeches and statues commemorating Columbus, along with a critical rethinking of his life and legacy.

But the question remains, how did a man who never set foot on North America get a federal holiday in his name? While Columbus did arrive in the "New World" when he cast anchor in the Bahamas, he never made it to the United States.

This is in contrast to Juan Ponce de Leon (who arrived in Florida in 1513), Alonso Alvarez de Pineda (whose ships arrived in what's now known as Corpus Christi Bay in Texas in 1519) and fellow Italian Giovanni da Verrazzano, who reached New York Harbor in 1524.

So why Columbus Day? Until the mid-1700s, Christopher Columbus was not widely known among most Americans. This began to change in the late 1700s, after the United States gained independence from Britain. The name "Columbia" soon became a synonym for the United States, with the name being used for various landmarks in the newly created nation (see the District of Columbia, Columbia University and the Columbia River).

Writer Washington Irving's A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, published in 1828, is the source of much of the glorification and myth-making related to Columbus today and is considered highly fictionalized.

For example, Irving's portrayal of Columbus is of a benevolent, adventurous man who was known for his generosity to Indians. In the best-seller, Columbus "was extremely desirous of dispelling any terror or distrust that might have been awakened in the island by the pursuit of the fugitives," after the escape of a group of Indian captives. This, of course, is the complete opposite of Columbus' actual behavior toward native people. (Incidentally, A History of the Life was also responsible for the incorrect belief that most people thought the Earth was flat until after Columbus's journey.)

Anti-Italian Sentiment

While Italians had always been a part of American history, it wasn't until the 1820s that Italian immigrants began moving to the United States in sizable numbers. The largest wave of Italian immigration occurred between 1880 and the start of World War I in 1914.

As Italian-Americans began to settle in the country's major cities, they often faced religious and ethnic discrimination. As Andrew Rolle wrote in his book, The Italian Americans: Troubled Roots, Italians were often portrayed as "short of stature, dark in complexion, cruel and shifty." Newspaper reports at the time often used the word "swarthy" to refer to Italians and other language of the time focused on the foreignness (and Catholic-ness) of these new Americans.

These anti-Italian sentiments occasionally led to brutal violence. One of the largest mass lynchings in the United States occurred in New Orleans in 1891, when 11 Sicilian immigrants were lynched after the city's police commissioner was killed and suspicion had been placed on the Italian community. (The 11 men had been found not guilty before the lynching. A New York Times editorial had this reaction: "Yet while every good citizen will readily assent to the proposition that this affair is to be deplored, it would be difficult to find any one individual who would confess that privately he deplores it very much.")

The first official commemoration of Columbus' journey occurred in 1892, just a year after the New Orleans lynchings. That's when President Benjamin Harrison became the first president to call for a national observance of Columbus Day, in honor of the 400th anniversary of Columbus' arrival. Harrison's proclamation directly linked the legacy of Columbus to American patriotism, with the proclamation celebrating the hard work of the American people and Columbus equally:

"On that day let the people, so far as possible, cease from toil and devote themselves to such exercises as may best express honor to the discoverer and their appreciation of the great achievements of the four completed centuries of American life."

Harrison's proclamation is notable in that there are no real references to Columbus' life, work or nationality. Instead, it was very specific to the 400th anniversary of Columbus' journey and how far America as a whole had come since then.

Celebrating Heritage, Via Columbus

Because Italian-Americans were struggling against religious and ethnic discrimination in the United States, many in the community saw celebrating the life and accomplishments of Christopher Columbus as a way for Italian Americans to be accepted by the mainstream. As historian Christopher J. Kauffman once wrote, "Italian Americans grounded legitimacy in a pluralistic society by focusing on the Genoese explorer as a central figure in their sense of peoplehood."

The first state to officially observe Columbus Day was Colorado in 1906. Instrumental in the creation of the holiday was Angelo Noce, an Italian immigrant who was the founder of Colorado's first Italian newspaper, La Stella.

Noce and fellow Italian-American Siro Mangini dreamed of honoring Christopher Columbus and worked with Colorado's first Hispanic state Sen. Casimiro Barela, to sponsor a bill proposing a Columbus Day holiday. (Interestingly, Siro Mangini owned a tavern named after Columbus. As his daughter recalled, "He finally decided to call it Christopher Columbus Hall, thinking that he was [the] one Italian [that] Americans would not throw rocks at.") Within five years of Colorado's creating the holiday, 14 other states were also celebrating Columbus Day.

Not everyone was happy about the possibility of a national holiday to honor Columbus. Around the same time people like Angelo Noce were working to make Columbus Day happen, there was also a movement going on to promote the Viking explorer Leif Erikson.

In 1925, while marking the centennial of the first arrival of Norwegian immigrants to the United States, President Calvin Coolidge told a crowd of thousands at the Minnesota State Fair that he believed that Erikson was the first European to discover America. Erikson is believed to have arrived in what is now Newfoundland, Canada, about 500 years before Columbus' arrival. This belief is supported by old Norse sagas that say the Vikings reached North America around the year 1000.

In 1930, Wisconsin became the first state to observe Leif Erikson Day. (The day would become a national day of observance in 1954 and falls on Oct. 9. President Obama's 2013 declaration can be read here.)

It wasn't until 1934 that Columbus Day became a federal holiday during Franklin Roosevelt's administration. The Knights of Columbus, a Catholic fraternal service organization, was instrumental in the creation of the holiday, (founded in 1882, the organization named itself after Columbus as a way to reflect that Roman Catholics were always part of American life.) In 1970, Congress declared it would be the second Monday of October.

Exploring Alternatives

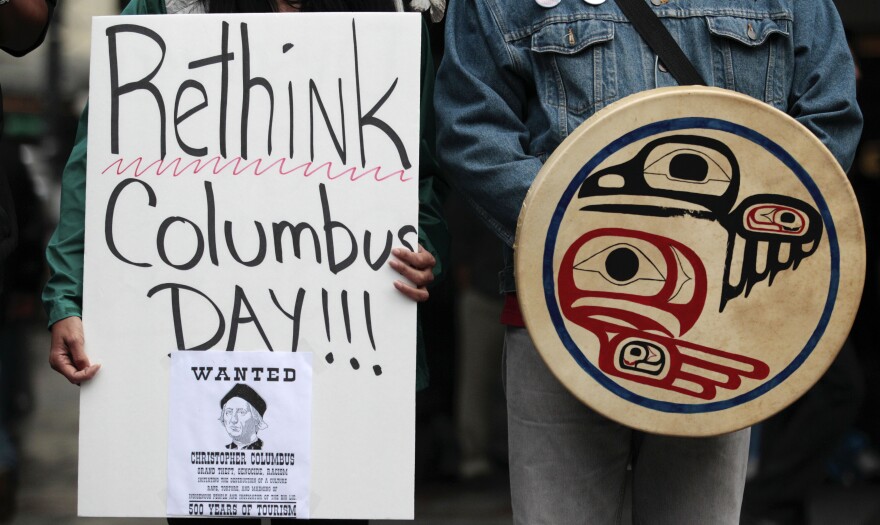

Since the 1970s, Columbus' life and legacy has been examined much more critically by academics and the general public alike, and the mixed feelings now associated with the day reflect that. According to historian Matthew Dennis, "Within 50 years of 1492, the Greater Antilles and Bahamas saw their population reduced from an estimated million people to about 500." That's a shocking statistic.

Three states with significant native populations — Hawaii, Alaska and South Dakota — do not observe the day at all. In 1990, South Dakota decided to celebrate "Native American Day" instead. In Hawaii, the state choses to celebrate "Discoverers' Day" and its Polynesian community on the second Monday of October. Alaska is said not to celebrate the day because it falls too close to Alaska Day (Oct. 18). And the city of Berkeley, Calif., declared in 1992 that it would be celebrating "Indigenous Peoples Day" on the same day the rest of the country would be celebrating Columbus.

Throughout all of these discussions and changes, Columbus Day remained a celebration of Italian-American pride. Perhaps the best known pop culture reference to this pride is the 2002 Sopranos episode "Christopher," in which Silvio becomes incensed at a planned Native American Columbus Day protest and plans to take action.

In 2009, Nu Heightz Cinema released a PSA entitled "Reconsider Columbus Day," urging people to reflect on Columbus's true legacy. "With all due respect," the various Native American narrators intoned, "there's been an ugly truth that has been overlooked for way too long."

And last week, Matthew Inman, the founder and cartoonist of The Oatmeal, illustrated the history of Columbus' time in the Bahamas, with an emphasis on the natives he enslaved (Inman calls Columbus "the father of the Transatlantic Slave Trade") and notes that Columbus' goal was to acquire as much gold as possible. Inman instead suggests that Americans should celebrate the life and career of fellow explorer Bartolomé de las Casas. De las Casas, like Columbus, originally participated in the slave trade, but later repented and devoted his life to defending indigenous people's rights.

Whatever you think of Columbus Day, most people would probably agree with this writer for The Star Ledger, who recently noted that "if there's a more embattled holiday on the calendar than Columbus Day, I'd be hard pressed to find it."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.